I get the odd email from people asking how Sudoku Grab works. I’ve replied to quite a few individually, but I thought it would be much easier to just explain it on the blog. Also when I demo the app people are often amazed (and equally, some people are also often not amazed…).

For the ones that are amazed they can get a bit enthusiastic and start coming up with all sorts of amazing ideas on what you could do with “the technology”. I then have to explain to them that it’s actually not doing anything really clever and that their idea might actually be quite a hard problem in comparison.

Sudoku Grab is a collection of some fairly basic image processing techniques that most engineering students at University could probably figure out how to put together. All of the algorithms used are either commonly available and can be found on the internet or can be written pretty easily. Obviously tweaking them and getting them all running together seamlessly is the real trick…

A good source to get started with is the OpenCV library which can be compiled on most platforms (including the iPhone). I wish I’d been aware of it before I started this project as it would have saved quite a bit of time.

One of the things that makes recognizing Sudoku puzzles an easier task than most image processing/recognition problem is that it is a highly constrained problem - a standard Sudoku puzzle is going to be a square grid and it will only contain the printed numbers 1-9.

These two points are very important. The first point - it’s a square grid tells us what shape a puzzle is and what we should be looking for in an image. The second point - it will only contain the printed numbers 1-9 tells us that we aren’t going to need a sophisticated OCR system. When we look at the problem there’s nothing that jumps out and says “nobody has solved this before - it’s probably really hard”.

We can also add some additional assumptions -

- In a photograph of a sudoku puzzle, the puzzle is going to be the main/most important object on the page A user is going to be photographing the puzzle - they aren't going to take a picture of a whole newspaper page, they won't be taking a photograph of a coffee shop and expecting us to find a sudoku puzzle that someone is playing four tables away. Also, the user is going to try and capture the whole puzzle, they won't miss a corner or chop off the top.

- The puzzle will be orientated reasonably correctly. No-one (hopefully) is going to be taking a picture of an upside down puzzle, and typically they will be trying to align it nicely in the camera viewfinder so it is reasonably straight without too much distortion.

So at the start of our Sudoku puzzle recognition we’d expect to be getting an image similar to this one:

We can see that this meets all the assumption above. We’ve got the whole puzzle - there are no bits missing, the puzzle is reasonably straight - it’s not upside down or at some crazy angle, it’s also the main thing in the picture - there’s not a lot of distraction in the image, it’s just a picture of a sudoku puzzle.

So, how are we going to go about recognising this image? There are basically 4 main problems to tackle:

- Where is the puzzle?

- Once i've found the puzzle how do I turn it back into a square puzzle?

- I've got the puzzle - how do I find the numbers?

- How do I recognise the numbers?

Let’s look at each of these in turn:

1. Where is the puzzle?

The first thing to do in any image processing problem is to reduce the amount of data you are dealing with. We started from the full colour high resolution image. The first thing we can do is to throw away the colour information. Looking at our sample image, having colour does not add any information that is useful to us*.

What else can we see - an obvious thing is that this is a printed page, it’s basically a black and white image. So the first step in our image processing is to throw away even more information. We are going to threshold the image so that we have either background pixels (the paper) or foreground pixels (the printed elements).

There are a variety of thresholding techniques available to us: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thresholding_(image_processing)

The initial naive approach is the obvious one. Light pixels are the paper and dark pixels are the ink, so lets pick a number (say the average pixel value for the image) and anything less that that we’ll set as foreground and anything higher than that is background. This would give us an image that looks like this:

It’s kind of ok - there’s some paper showing up as foreground in the top left, but the puzzle is also showing up, but as we go down towards the bottom right the puzzle starts to break up. We can see that this simple approach doesn’t really handle variable lighting on the page. And we can imagine that if there are any shadows on the page the results will be even worse.

What we need is a thresholding method that can take account of this problem. My personal favourite is a simple adaptive threshold. For each pixel in the image take the average value of the surrounding area. If the pixel is less than 90% of this value then it is ink, if it is higher then it is paper. The reason for choosing 90% of the value is that this lets us filter out flat areas or areas that aren’t changing very much (ie blank bits of paper or solid black sections).

This results in the image shown below:

As you can see it’s a lot better than the previous attempt.

We can now apply one of our assumptions: “In a photograph of a sudoku puzzle, the puzzle is going to be the main/most important object on the page” - we can interpret this in the following way - the most important thing on the page probably has the most foreground pixels. So let’s extract every blob of set pixels and see which blob has the most. That blob of pixels must be our Sudoku Puzzle. To do this we’ll using a blob extraction algorithm.

The simplest way of doing this is to scan through the image looking for a set pixel. Every time we find a set pixel we perform a “flood fill”. The pixels that we fill in make up our blob.

Running this process and then taking the blob with the largest number of pixels gives us this image:

So, that’s great, we’ve managed to go from an picture of a puzzle in a newspaper to finding the pixels which are probably part of a Sudoku puzzle. Most importantly we have the pixels that make up the outside frame of the puzzle. Now what?

So, that’s great, we’ve managed to go from an picture of a puzzle in a newspaper to finding the pixels which are probably part of a Sudoku puzzle. Most importantly we have the pixels that make up the outside frame of the puzzle. Now what?

Ideally it would nice if we knew the coordinates of the corners of the puzzle frame - that would let use draw a box around it and know the exact location of it. There are quite a few ways that we could approach this. A simple approach might be to scan through the pixels looking for the top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right. That might work. I’ve chosen to use one of my favourite algorithms; the Hough transform.

This algorithm can be used to detect straight lines (and many other shapes) in an image - and rather handily, straight lines is what make up a Sudoku Grid. So let’s feed our extracted grid pixels into a Hough transform. This gives us this (this is a representation of the results of the Hough transform mapped back into an image so we can see it):

You can have a play with hough transforms here.

This image represents all the possible lines that are in our image. The x coordinate is the angle of the line and the y coordinate is the distance of the line from the origin (I’ve trimmed the image to make it a bit smaller so our y coordinate looks a bit smaller than it would normally).

We can see that we have a bunch of peaks around 0 and 180 degress mark (on the left and the right of the image) and a bunch of peaks in the midle of the image, around the 90 degrees mark. These correspond to horizontal and vertical lines in the image.

We really only care about the leftmost, rightmost, topmost and bottommost lines. These correspond to the peaks at the top and bottom of the two groups.

If we take these peaks and turn them back into lines we have the lines along the top, bottom, left and right of the puzzle - find where they intersect and we have the corner coordinates of the puzzle. This let’s us produce the image you can see here:

We now know exactly where in the original image we have found the Sudoku puzzle!

2. Once i've found the puzzle how do I turn it back into a square puzzle?

So, we’ve got the corner points of the puzzle - it’s currently not really usable for much - it’s a bit distorted. What we need is some way of mapping from the puzzle in the picture back into a square puzzle.

We need a transform that will maps one arbitrary 2D quadrilateral into another. For this we can use a perspective transform:

This will map a point given by x,y in one quadrilateral into a new point X,Y in another quadrilateral. As you can see there are 8 unknowns in these two equations - but fortunately we have 8 values (the corner x and y coordinates of the puzzle and our arbitrary x and y corner points of our square image). Solving these equations gives us the a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h which provide us with a mapping to get our puzzle out nice and straight:

You can find a lot more information on this approach here (there is of course a trick to doing this - you don’t really have to solve 8 simultaneous equations using a bit of paper! This article describes how to do it using matrices - or OpenCV has this all built in). I won’t go into it in detail as to be honest it’s completely beyond my comprehension…

You can find a lot more information on this approach here (there is of course a trick to doing this - you don’t really have to solve 8 simultaneous equations using a bit of paper! This article describes how to do it using matrices - or OpenCV has this all built in). I won’t go into it in detail as to be honest it’s completely beyond my comprehension…

3. I've got the puzzle - how do I find the numbers?

So we’re pretty good - we’ve now got an undistorted square Sudoku puzzle. That’s good, but it doesn’t really help us that much - we could have got this far by making the user line up the puzzle with a square shape in the viewfinder when they took the picture!

Let’s try and see which boxes in the puzzle actually have numbers in - this is actually pretty straightforward, all we have to is divide the puzzle into a set of boxes threshold each box and apply the blob extraction algorithm to the middle of the box. If we manage to extract a blob then it’s more than likely that the box must contain a number. Throw away the empty boxes and you’ve got the numbers that you need to recognise.

4. How do I recognise the numbers?

We can now take the blobs from the previous stage and try and work out what numbers they represent - this is where the world becomes your oyster. There are a huge number of techniques for performing OCR.

And a huge number of non-specific pattern recognition algorithms.

For my implementation I chose to use a Neural Network. I collected a large number of extracted number images from some sample puzzles and hand classified them. I then used these to train a simple neural network to recognise the digits 1-9. This works remarkably well, but I suspect I am probably using a hammer to crack a nut in this instance…

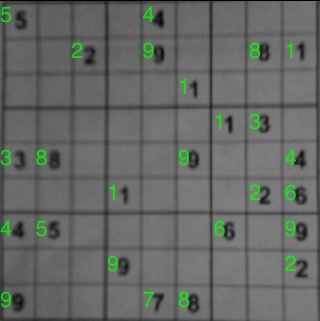

Anyway - this gives us our final result - a Sudoku puzzle with recognised numbers!

There are a huge number of improvements that can be made to these basic steps. You can add intelligence at every step to improve your chances of recognising a puzzle.

But basically, that’s it!